Table of Contents

Introduction

Uterine cancer, particularly endometrial cancer, represents a significant concern in women’s health due to its prevalence as one of the most common gynecological malignancies. The rising incidence, especially in developed nations, emphasizes the importance of a deep understanding of the disease, including its risk factors, symptoms, diagnostic procedures, and management strategies. Addressing these aspects is crucial for improving patient outcomes and developing effective prevention strategies.

Endometrial cancer is primarily a disease of postmenopausal women, although it can affect younger women, particularly those with risk factors such as obesity or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). As the population ages and obesity rates increase globally, the burden of endometrial cancer is expected to rise, necessitating more comprehensive public health strategies and advances in clinical care.

Understanding Uterine and Endometrial Cancer

What is Endometrial Cancer?

Endometrial cancer originates in the lining of the uterus, known as the endometrium, and constitutes about 90% of all uterine cancers. It is essential to differentiate between the types of endometrial cancer as this influences treatment approaches and patient prognosis. The endometrium is a hormonally responsive tissue, and the imbalance in hormonal levels, particularly estrogen, plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of the disease.

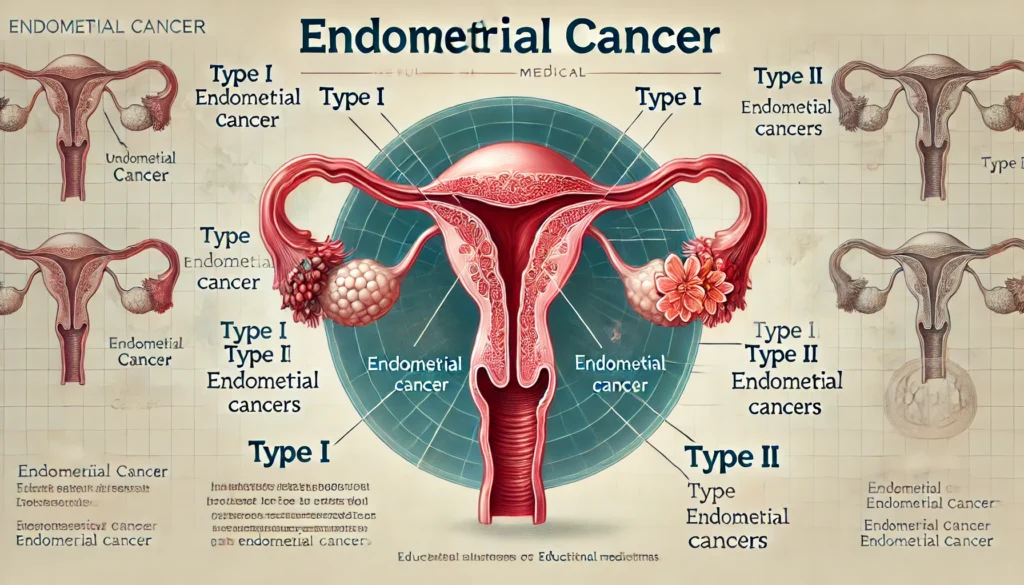

The disease is categorized into two main histological types, which are critical for determining the treatment plan and predicting outcomes. Type I endometrial cancer, which is estrogen-dependent, tends to have a better prognosis compared to Type II, which is more aggressive and not related to estrogen exposure. This distinction is vital for clinicians when developing a treatment strategy, as it influences decisions regarding the extent of surgery and the need for adjuvant therapy.

Types of Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial cancer is classified into two primary types, each with distinct characteristics:

- Type I Endometrial Cancer: Type I endometrial cancer is the most common form, accounting for approximately 70% to 80% of cases. It is typically associated with excess estrogen exposure, either endogenous or exogenous, often occurring in premenopausal or perimenopausal women. These tumors are generally low-grade endometrioid adenocarcinomas, which tend to grow slowly and are less likely to spread beyond the uterus. Consequently, they have a favorable prognosis when detected early. The link between estrogen and Type I tumors underscores the importance of hormonal balance in disease prevention (Braun, Overbeek-Wager, & Grumbo, 2016).

- Type II Endometrial Cancer: Type II endometrial cancer is less common but significantly more aggressive. It includes high-grade tumors such as serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and other non-endometrioid histologies. Unlike Type I, Type II cancers are not related to estrogen exposure and are more likely to occur in older, postmenopausal women. These tumors are more prone to spread to lymph nodes and distant organs, making them more challenging to treat and leading to a poorer prognosis. Understanding the molecular and genetic differences between these types is crucial for developing targeted therapies (Braun et al., 2016; Morice et al., 2016).

Read: Can a Narcissist Change? An In-depth Analysis

Risk Factors and Epidemiology

Key Risk Factors

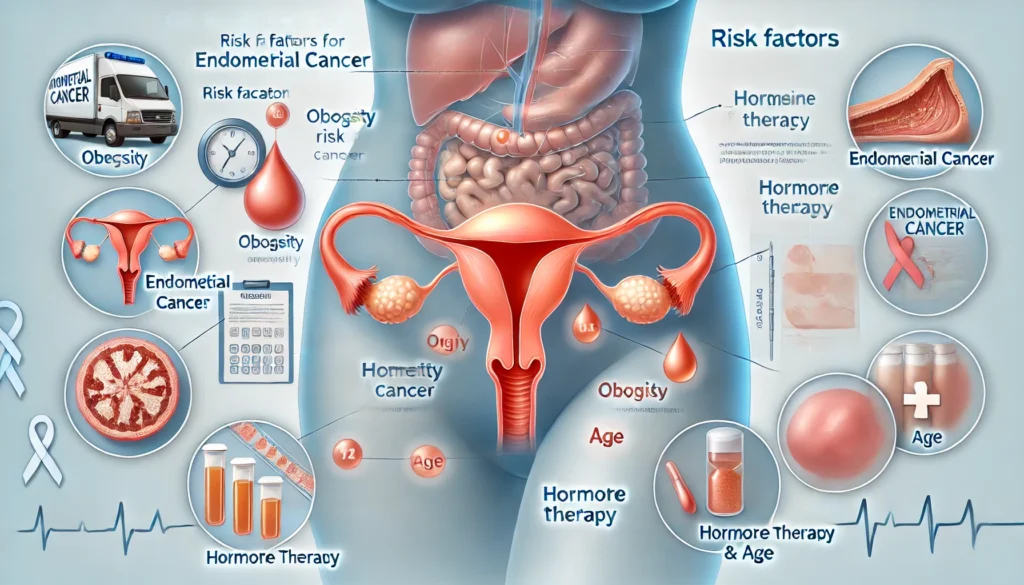

Endometrial cancer is influenced by several risk factors, some of which are modifiable through lifestyle changes, while others are inherent. Understanding these risk factors is essential for prevention and early detection strategies:

- Unopposed Estrogen Exposure: The most significant risk factor for endometrial cancer is prolonged exposure to estrogen without the counterbalancing effect of progesterone. This can occur in various scenarios, such as hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with estrogen alone, early menarche, late menopause, or conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Estrogen stimulates the endometrial lining, and without the protective effect of progesterone, this can lead to hyperplasia and eventually cancer. This mechanism highlights the importance of hormonal balance in reducing cancer risk (Braun et al., 2016).

- Obesity: Obesity is a major risk factor for endometrial cancer, contributing to nearly 40% of cases. Adipose tissue is a significant source of estrogen production, especially after menopause, when the ovaries cease to produce hormones. This excess estrogen promotes the growth of the endometrium, increasing the risk of cancerous changes. Furthermore, obesity is associated with chronic inflammation and insulin resistance, both of which are implicated in cancer development. The growing prevalence of obesity worldwide suggests that endometrial cancer rates may continue to rise (Wright et al., 2012).

- Age and Family History: The risk of endometrial cancer increases with age, with most cases diagnosed in women over 50. Additionally, a family history of endometrial cancer or related conditions, such as Lynch syndrome, significantly raises an individual’s risk. Lynch syndrome, an inherited disorder, increases the risk for several cancers, including endometrial cancer, and women with this condition should be closely monitored. Genetic counseling and regular screening can help manage the risk in these high-risk groups (Morice et al., 2016).

Global Incidence and Mortality

Globally, the incidence of endometrial cancer is rising, with the highest rates observed in North America and Europe. These regions have seen a steady increase in cases, likely due to lifestyle factors such as obesity, diet, and physical inactivity. Conversely, regions with lower incidence rates, such as parts of Asia and Africa, often report higher mortality rates, reflecting disparities in healthcare access, early detection, and treatment availability. Understanding these epidemiological trends is crucial for global health initiatives aimed at reducing the burden of endometrial cancer through prevention, early detection, and treatment improvements (Morice et al., 2016).

Read: Chordae Tendineae 101: Structures and Functions

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Common Symptoms

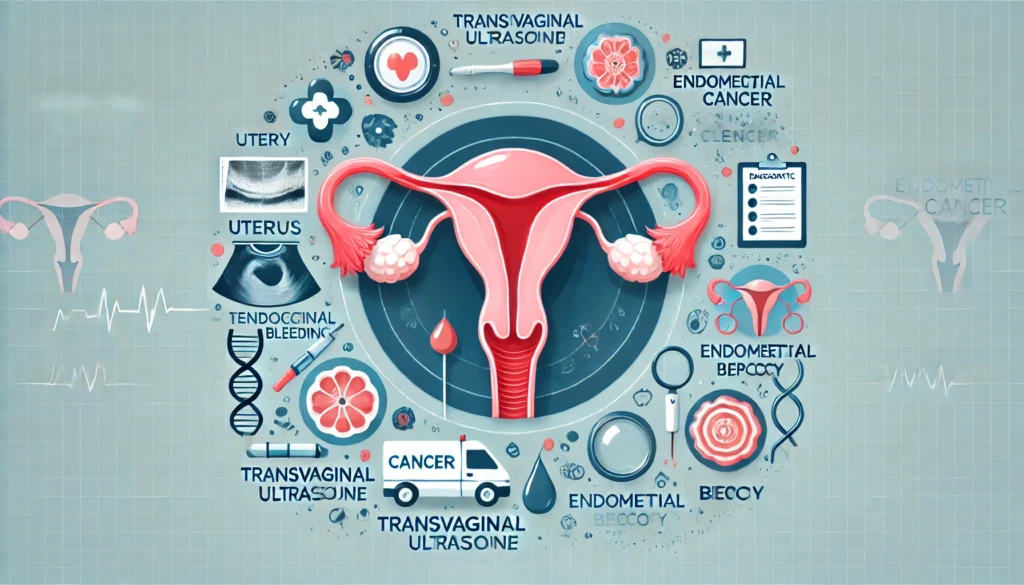

The most common symptom of endometrial cancer is abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), particularly postmenopausal bleeding. Approximately 75% of women with endometrial cancer present with this symptom at the time of diagnosis (Kimura, Kamiura, & Yamamoto, 2004). Premenopausal women may experience heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding. While AUB is a key indicator of endometrial cancer, it can also be associated with other gynecological conditions, making it essential for women experiencing these symptoms to undergo a thorough evaluation.

In addition to abnormal bleeding, other symptoms of endometrial cancer may include pelvic pain, unexplained weight loss, and difficulty or pain during urination or intercourse. These symptoms often indicate more advanced disease, underscoring the importance of early detection and intervention. Women should be educated about these symptoms and encouraged to seek medical advice promptly if they experience any unusual changes in their menstrual cycle or overall health.

Early Detection Methods

Early detection of endometrial cancer is critical for improving survival rates. Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) is often the first-line diagnostic tool used to assess endometrial thickness. A thickness greater than 5 mm in postmenopausal women typically warrants further investigation, as this can be an early sign of hyperplasia or cancer. However, TVUS alone is not definitive; therefore, an endometrial biopsy is considered the gold standard for diagnosis. This procedure involves sampling the endometrial tissue and analyzing it for malignant cells, providing a clear diagnosis (Braun et al., 2016).

The role of hysteroscopy, where a small camera is used to visualize the inside of the uterus, is also increasingly recognized in the diagnostic process. Hysteroscopy allows for direct visualization of the endometrium and can help identify suspicious areas that might be missed by TVUS or biopsy alone. When combined with biopsy, hysteroscopy enhances diagnostic accuracy, particularly in complex cases or when initial biopsy results are inconclusive.

Screening Guidelines

Routine screening for endometrial cancer is not generally recommended for asymptomatic women, as the benefits of such screening in the general population are not well established. However, for women at high risk—such as those with Lynch syndrome or a strong family history of endometrial cancer—annual screening is recommended, starting at age 35. Screening typically involves endometrial biopsy or TVUS, aiming to detect cancer at an early, more treatable stage. Educating high-risk women about their increased risk and the importance of regular monitoring is crucial for early detection and prevention of advanced disease (Braun et al., 2016).

Treatment Approaches

Surgical Options

Surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment for endometrial cancer, with the primary approach being total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of the uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes). This procedure is often curative for early-stage cancers confined to the uterus. In cases where the cancer is more advanced or has spread beyond the uterus, a more extensive surgical approach, including pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy (removal of lymph nodes), may be necessary to assess the extent of the disease and reduce the risk of recurrence (Wright et al., 2012).

Minimally invasive surgical techniques, such as laparoscopic or robotic-assisted surgery, are increasingly favored over traditional open surgery due to their numerous benefits. These include shorter hospital stays, reduced postoperative pain, quicker recovery times, and lower risk of complications. These techniques are particularly advantageous for obese patients, who are at a higher risk for surgical complications. However, the choice of surgical method should be individualized based on the patient’s overall health, cancer stage, and surgeon expertise.

Adjuvant Therapies

Adjuvant therapy, including radiation and chemotherapy, is often recommended following surgery, especially for patients with high-risk features, such as deep myometrial invasion, lymphovascular space involvement, or aggressive histological subtypes. Radiation therapy can be delivered externally (external beam radiation therapy) or internally (brachytherapy), depending on the extent and location of the disease. Radiation is particularly useful in reducing the risk of local recurrence, especially in patients with advanced disease or those who are not candidates for surgery (Morice et al., 2016).

Chemotherapy is typically reserved for advanced-stage or recurrent endometrial cancer and is often combined with radiation in a multimodal approach. Chemotherapeutic agents such as paclitaxel, carboplatin, and doxorubicin are commonly used, either alone or in combination. The choice of chemotherapy regimen depends on the cancer’s stage, histology, and the patient’s overall health. In recent years, there has been growing interest in targeted therapies and immunotherapies, which offer new hope for treating resistant or recurrent cases by focusing on specific molecular pathways involved in cancer progression.

Read:What is Leadership?

Prognosis and Survival

Survival Rates

The prognosis for endometrial cancer is generally favorable when the disease is detected early. The 5-year survival rate for women diagnosed with stage I endometrial cancer is approximately 90%, reflecting the high curability of the disease when confined to the uterus. However, survival rates decrease significantly as the disease advances, with stage IV cancer having a 5-year survival rate of less than 30%. These statistics highlight the critical importance of early detection and timely treatment (Wright et al., 2012).

Factors Influencing Prognosis

Several factors influence the prognosis of endometrial cancer, including the tumor’s stage at diagnosis, histological type, and patient characteristics such as age and comorbidities. The duration and timing of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) can also impact outcomes. While early detection through AUB often leads to better prognosis, a study by Kimura et al. (2004) found that survival rates do not significantly differ between patients with and without AUB, provided the cancer is detected and treated promptly. This suggests that other factors, such as tumor biology and patient health, may play a more critical role in determining outcomes.

Patient adherence to treatment and follow-up care is another important factor influencing prognosis. Regular monitoring for recurrence, managing side effects of treatment, and addressing comorbid conditions are crucial for improving long-term survival. Support from healthcare providers, patient education, and access to resources can help patients navigate the complexities of cancer treatment and recovery.

Prevention and Risk Reduction

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle modifications play a significant role in reducing the risk of endometrial cancer. Managing risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension is critical for prevention. Weight loss through diet and exercise not only reduces the risk of endometrial cancer but also improves overall health and quality of life. Regular physical activity, even moderate exercise, can help maintain a healthy weight, reduce estrogen levels, and lower cancer risk (Braun et al., 2016).

In addition to weight management, dietary choices can influence cancer risk. Diets rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and low in saturated fats and red meats, are associated with a lower risk of endometrial cancer. Limiting alcohol consumption and avoiding tobacco use are also important preventive measures, as both have been linked to an increased risk of various cancers. Public health campaigns and individual counseling can help raise awareness about the importance of healthy lifestyle choices in cancer prevention.

Hormonal Interventions

For women undergoing hormone replacement therapy (HRT), especially those with a uterus, the addition of progesterone to estrogen therapy is essential in reducing the risk of endometrial cancer. Estrogen alone can stimulate the growth of the endometrium, leading to hyperplasia and eventually cancer. By counteracting these effects, progesterone significantly lowers the likelihood of malignant transformations. The type, dosage, and duration of hormone therapy should be carefully considered and personalized to balance the benefits and risks (Braun et al., 2016).

In addition to HRT, the use of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) has been shown to reduce the risk of endometrial cancer. COCs provide a protective effect by regulating hormone levels and reducing the incidence of ovulatory cycles, which can lead to endometrial hyperplasia. This protective effect can last for many years after discontinuation of COCs, offering long-term benefits for women at risk.

Conclusion

Endometrial cancer remains a significant health issue, particularly in the context of rising obesity rates and an aging population. Early detection and timely intervention are key to improving survival outcomes. While the prognosis for early-stage endometrial cancer is generally favorable, ongoing research and advancements in treatment are essential for better management of advanced stages and high-risk cases. By understanding the risk factors, symptoms, and treatment options, healthcare providers can better guide patients in preventing and managing this common gynecological cancer.

Summary Table of Key Points

| Key Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Types of Endometrial Cancer | Type I (Estrogen-dependent, favorable prognosis) vs. Type II (Aggressive, poorer prognosis) |

| Risk Factors | Unopposed estrogen, obesity, age, family history |

| Common Symptoms | Abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, weight loss |

| Diagnostic Tools | Transvaginal ultrasonography, endometrial biopsy, hysteroscopy |

| Treatment Options | Surgery (hysterectomy), adjuvant therapies (radiation, chemotherapy) |

| Prognosis | 5-year survival rates: 90% for Stage I, <30% for Stage IV |

| Prevention | Lifestyle modifications, hormonal interventions (HRT, COCs) |

References

- Braun, M. M., Overbeek-Wager, E. A., & Grumbo, R. J. (2016). Diagnosis and management of endometrial cancer. American Family Physician, 93(6), 468-474.

- Kimura, T., Kamiura, S., & Yamamoto, T. (2004).Abnormal uterine bleeding and prognosis of endometrial cancer. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 87(1), 82-86.

- Morice, P., Leary, A., Creutzberg, C., Abu-Rustum, N., & Darai, E. (2016). Endometrial cancer. The Lancet, 387(10023), 1094-1108.

- Wright, J. D., Medel, N. I. B., Sehouli, J., Fujiwara, K., & Herzog, T. J. (2012). Contemporary management of endometrial cancer. The Lancet, 379(9823), 1352-1360.