Table of Contents

Magic mushrooms, commonly known as shrooms, have been used for centuries for their psychoactive effects (Aaronson 1970). These fungi contain the compound psilocybin, which the body converts into psilocin to produce hallucinogenic effects (Stamets 1996). Understanding how long these substances stay in your system is essential for users, healthcare providers, and researchers. This comprehensive article explores the duration shrooms stay in the system, factors affecting this duration, detection methods, effects, risks, and frequently asked questions.

Types of Magic Mushrooms and Their Psychoactive Compounds

Several species of mushrooms contain the psychoactive compounds psilocybin and psilocin. The most common types include:

- Psilocybe cubensis: Widely used and known for its moderate potency (Stamets 1996).

- Psilocybe semilanceata: Also known as liberty caps, these are more potent (Stamets 1996).

- Psilocybe azurescens: One of the most potent species, containing high levels of psilocybin and psilocin (Stamets 1996).

Duration of Psilocybin and Psilocin in the System

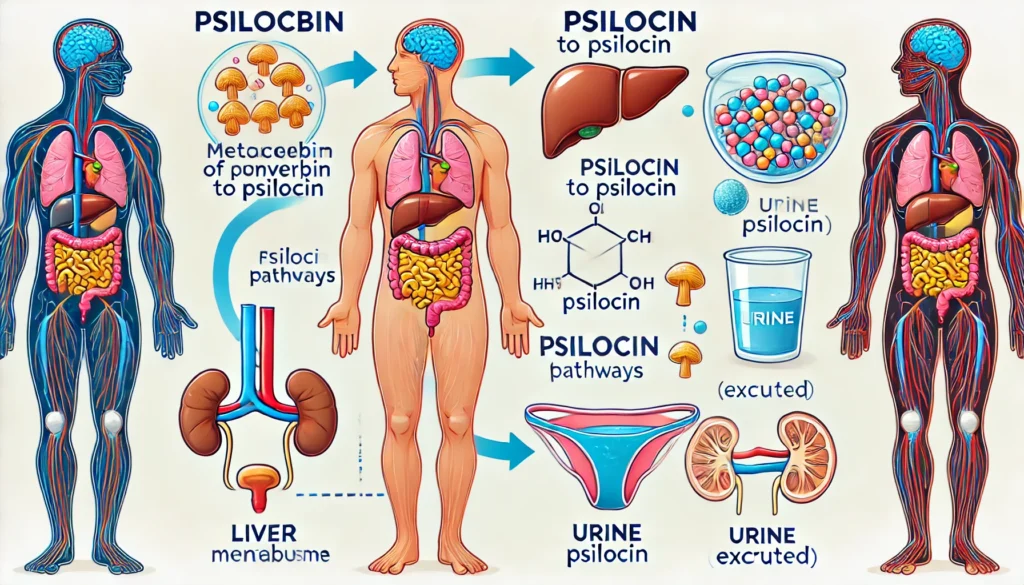

Metabolism and Elimination

Psilocybin is quickly converted into psilocin, which is the active compound. Psilocin is then metabolized in the liver and excreted through urine. The half-life of psilocin is approximately 1 to 3 hours, meaning that it takes this amount of time for the concentration of psilocin in the blood to reduce by half (Belouin and Henningfield 2018). This rapid metabolism explains why the psychoactive effects of shrooms generally last only a few hours.

Detection Times

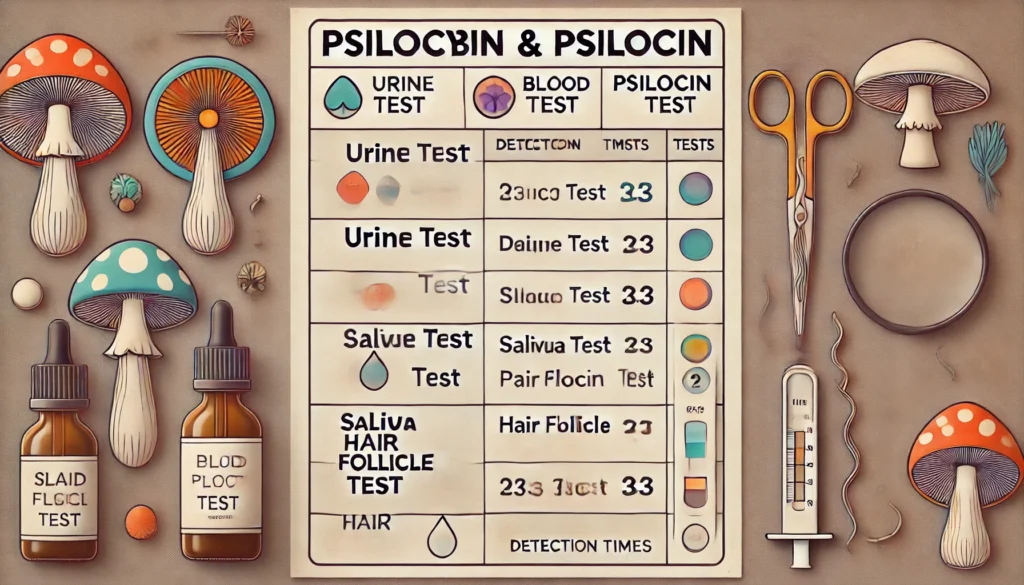

The detection time for psilocybin and psilocin can vary based on the type of test used:

- Urine Test: Psilocin can be detected in urine for up to 24 hours after ingestion. In some cases, traces can be found for up to 3 days, especially with higher doses or frequent use (Erritzoe et al. 2018).

- Blood Test: Psilocin is typically detectable in the blood for around 24 hours (Erritzoe et al. 2018).

- Saliva Test: This method is not commonly used but can detect psilocin for up to 24 hours (Erritzoe et al. 2018).

- Hair Follicle Test: Psilocin and psilocybin can be detected in hair follicles for up to 90 days. This test is less common due to its cost and complexity (Erritzoe et al. 2018).

Factors Influencing the Duration Shrooms Stay in the System

Several factors can affect how long shrooms stay in your system:

- Dosage: Higher doses can prolong the presence of psilocybin and psilocin in the body (Belouin and Henningfield 2018).

- Frequency of Use: Regular use can lead to accumulation, extending detection times (Belouin and Henningfield 2018).

- Metabolism: Individuals with faster metabolisms process and eliminate substances more quickly (Belouin and Henningfield 2018).

- Age and Health: Younger, healthier individuals often metabolize substances faster than older adults or those with health issues (Belouin and Henningfield 2018).

- Body Mass: Individuals with higher body mass may process substances differently, potentially affecting detection times (Belouin and Henningfield 2018).

Effects of Shrooms

The effects of magic mushrooms can vary based on the dose, individual physiology, and setting. Common effects include:

- Euphoria: A sense of well-being and happiness (Aaronson 1970).

- Hallucinations: Visual and auditory distortions (Aaronson 1970).

- Altered Perception of Time: Time may appear to speed up or slow down (Aaronson 1970).

- Spiritual Experiences: Feelings of interconnectedness and profound insights (Aaronson 1970).

Side Effects

While many users report positive experiences, shrooms can also cause adverse effects, such as:

- Nausea and Vomiting: Common during the onset of effects (Aaronson 1970).

- Anxiety and Paranoia: Especially in higher doses or in a negative setting (Aaronson 1970).

- Confusion and Disorientation: Difficulty focusing or maintaining a coherent thought process (Aaronson 1970).

Risks and Long-Term Effects

Psychedelic mushrooms are generally considered to be low in toxicity, but they do carry risks:

- Psychological Distress: Bad trips can lead to intense fear, anxiety, or paranoia (Aaronson 1970).

- Flashbacks: Some users experience Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD), where they have flashbacks of their hallucinogenic experiences (Aaronson 1970).

- Potential for Abuse: Although not physically addictive, psychological dependence can develop (Aaronson 1970).

Read: Understanding the Intertubercular Groove

Detection Methods and Their Efficacy

Urine Testing

Urine testing is the most common method for detecting psilocybin use. It is non-invasive and can detect the presence of psilocin for up to 24-48 hours post-ingestion. The detection window may be longer for habitual users or those who have consumed large doses (Erritzoe et al. 2018).

Blood Testing

Blood tests are less common but can provide a more accurate measure of current intoxication. Psilocin is detectable in blood for up to 24 hours after use. Due to the short detection window, blood tests are usually used in situations where immediate impairment is suspected (Erritzoe et al. 2018).

Saliva Testing

Saliva tests are rarely used for detecting psilocybin or psilocin. When they are used, psilocin can be detected within 24 hours of ingestion. These tests are not as reliable due to variability in saliva production and composition (Erritzoe et al. 2018).

Hair Follicle Testing

Hair follicle tests can detect psilocybin and its metabolites for up to 90 days after use. This method is the most reliable for long-term detection but is also the most expensive and invasive. It involves collecting hair samples and analyzing them for trace amounts of psilocybin metabolites (Erritzoe et al. 2018).

| Test Type | Detection Time |

| Urine Test | Up to 24 hours |

| Blood Test | Up to 24 hours |

| Saliva Test | Up to 24 hours |

| Hair Follicle Test | Up to 90 days |

Long-Term Effects and Considerations

While the immediate effects of shrooms are well-documented, long-term effects are still under research. Some users report lasting positive changes, such as increased openness and a sense of connection with nature. However, there are also potential risks, including:

- Persistent Psychological Effects: Conditions such as Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD) can cause lasting visual disturbances (Aaronson 1970).

- Mental Health Risks: Individuals with a history of mental health issues may experience worsening symptoms or new psychiatric conditions (Erritzoe et al. 2018).

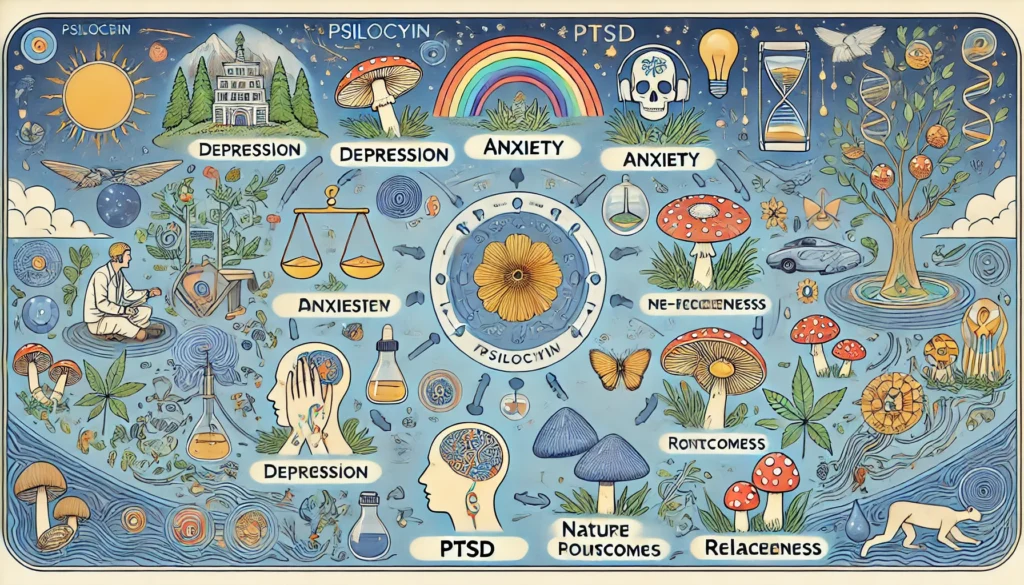

Figure 2: Long-Term Effects of Psilocybin Use

Case Studies and Research Findings

Recent research has delved into the potential therapeutic benefits and risks associated with psilocybin. For instance, studies have shown that psilocybin may help in treating conditions like depression, anxiety, and PTSD (Carhart-Harris et al. 2018). These studies highlight the importance of context and setting in psychedelic experiences, emphasizing that supportive environments can enhance positive outcomes (Carhart-Harris et al. 2018).

A notable study by Lyons and Carhart-Harris (2018) found that psilocybin-assisted therapy resulted in increased nature-relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views. This suggests that psilocybin can have profound impacts on personality and worldview, even beyond the immediate hallucinogenic effects.

| Condition | Outcome |

| Depression | Significant symptom reduction |

| Anxiety | Reduced anxiety levels |

| PTSD | Improved coping mechanisms |

| Nature-relatedness | Increased connection with nature |

| Authoritarian views | Decreased authoritarianism |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How Long Do the Effects of Shrooms Last?

The effects of shrooms typically last between 4 to 6 hours, depending on the dose and individual metabolism. Some residual effects can last up to 12 hours (Erritzoe et al. 2018).

2. Can Shrooms Be Detected in a Standard Drug Test?

Most standard drug tests do not screen for psilocybin or psilocin. Specialized tests are required to detect these compounds (Erritzoe et al. 2018).

Read: What is Cystolitholapaxy?

3. How Long Before Shrooms Are Out of My System for a Drug Test?

For most urine and blood tests, shrooms are undetectable after 24 hours. However, hair follicle tests can detect psilocin for up to 90 days (Erritzoe et al. 2018).

4. What Should I Do if I Experience a Bad Trip?

If you experience a bad trip, try to stay calm and remind yourself that the effects are temporary. Seeking a safe and comfortable environment and having a sober friend can help. In severe cases, professional medical help may be necessary (Aaronson 1970).

Legal and Ethical Considerations

Legal Status

The legal status of psilocybin mushrooms varies worldwide. In many countries, including the United States, psilocybin is classified as a Schedule I controlled substance, meaning it is illegal to possess, distribute, or use it. However, some regions have decriminalized or legalized its use for therapeutic purposes. For example, Oregon has legalized psilocybin therapy for mental health treatment (Hausfeld 2020).

Read: Is Heel Pain a Sign of Cancer?

Ethical Considerations

The use of psilocybin mushrooms raises several ethical considerations, particularly regarding consent, mental health, and cultural sensitivity. Ensuring that individuals are fully informed about the potential risks and benefits is crucial. Additionally, the cultural significance of these substances to indigenous groups should be respected and preserved (George et al. 2019).

Social and Cultural Impacts

Indigenous Use

Indigenous cultures have used psilocybin mushrooms for centuries in religious and healing ceremonies. These practices are deeply embedded in their traditions and spiritual beliefs. The Mazatec people of Mexico, for example, have a rich history of using psilocybin mushrooms in shamanic rituals (Sabina and Wasson 1974).

Modern Usage

In contemporary society, the use of psilocybin mushrooms has expanded beyond traditional settings to include recreational use and experimental therapy. The resurgence of interest in psychedelics is partly driven by growing evidence of their therapeutic potential (Pollan 2018). However, this has also led to concerns about cultural appropriation and the commercialization of sacred plants (Fotiou 2016).

List of Factors Affecting Detection Times

- Dosage

- Frequency of Use

- Metabolism

- Age and Health

- Body Mass

Conclusion

Understanding how long shrooms stay in your system is crucial for both users and medical professionals. While psilocybin and psilocin are rapidly metabolized and eliminated, detection windows can vary based on several factors. Awareness of the effects, risks, and detection methods is crucial for users and healthcare providers. Psilocybin mushrooms hold significant therapeutic potential, but their use must be approached with caution and respect for cultural contexts.

References

- Aaronson, Bernard. 1970. Psychedelics: The Uses and Implications of Hallucinogenic Drugs. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Adams, Matthew. 2020. ‘Could Psychedelics Help Us Resolve the Climate Crisis?’ The Conversation. 28 January 2020.

- Aixalà, Marc, et al. (2018).‘Psychedelics and Personality’. ACS Chemical Neuroscience 9 (10): 2304–6.

- Alfred, Taiaiake, and Jeff Corntassel. 2005. ‘Being Indigenous: Resurgences against Contemporary Colonialism’. Government and Opposition 40 (4): 597–614.

- Arregi, Joseba. 2021. ‘Plastic Shamans, Intellectual Colonialism and Intellectual Appropriation in New Age Movements’. The International Journal of Ecopsychology (IJE) 2 (1).

- Austin, Paul. 2019.‘Soltara Healing Center Review – Retreat Center in Costa Rica’. Third Wave (blog). 28 June 2019.

- Bakker, Karen. 2010. ‘The Limits of “Neoliberal Natures”: Debating Green Neoliberalism’. Progress in Human Geography 34 (6): 715–35.

- Baudrillard, Jean. 1981. For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign. St. Louis, MO: Telos Press.

- Bauman, Richard, and Charles L. Briggs. 1990. ‘Poetics and Performances as Critical Perspectives on Language and Social Life’. Annual Review of Anthropology 19 (1): 59–88.

- Belouin, Sean J., and Jack E. Henningfield. 2018. ‘Psychedelics: Where We Are Now, Why We Got Here, What We Must Do’. Neuropharmacology 142 (November): 7–19.

- Benzinga. 2020. ‘Cybin Corp: Canada’s Largest Go-Public Financing In The Psychedelics Sector’. Benzinga. 27 October 2020.

- Bloomberg. 2020. ‘Multi-Billion-Dollar Market Forecast in Psychedelic Therapeutics’. Bloomberg.Com, 14 October 2020.

- Bogner, A., B. Littig, and W. Menz. 2009. Interviewing Experts. Springer.

- Bryman, Alan. 2012. Social Research Methods, 4th Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Byskov, Morten Fibieger. 2019. ‘Focusing on How Individuals Can Stop Climate Change Is Very Convenient for Corporations’. Fast Company. 11 January 2019.

- Carhart-Harris, Robin L, et al. 2018.‘Psychedelics and the Essential Importance of Context’. Journal of Psychopharmacology 32 (7): 725–31.

- Casaló, Luis V., and José-Julián Escario. 2018.‘Heterogeneity in the Association between Environmental Attitudes and Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Multilevel Regression Approach’. Journal of Cleaner Production 175 (February): 155–63.

- Castree, Noel. 2003. ‘Commodifying What Nature?’ Progress in Human Geography 27 (3): 273–97.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 1983. ‘The Grounded Theory Method: An Explication and Interpretation’. In Contemporary Field Research: A Collection of Readings, edited by Robert M. Emerson, 368.

- Cronon, William. 1996. ‘The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature’. Environmental History 1 (1): 7.

- Crutzen, Paul J. 2006. ‘The “Anthropocene”’. In Earth System Science in the Anthropocene, edited by Eckart Ehlers and Thomas Krafft, 13–18. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

- Dean, Bartholomew. 2009. Urarina Society, Cosmology, and History in Peruvian Amazonia. Gainesville, Fla.: University Press of Florida.

- Dev, Laura. 2018. ‘Plant Knowledges: Indigenous Approaches and Interspecies Listening Toward Decolonizing Ayahuasca Research’. In Plant Medicines, Healing and Psychedelic Science, edited by Beatriz Caiuby Labate and Clancy Cavnar, 185–204.

- Erritzoe, D., et al. 2018. ‘Effects of Psilocybin Therapy on Personality Structure’. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 138 (5): 368–78.

- Escobar, Arturo. 2007.‘WORLDS AND KNOWLEDGES OTHERWISE: The Latin American Modernity/Coloniality Research Program’. Cultural Studies 21 (2–3): 179–210.

- Folke, Carl, et al. 2011. ‘Reconnecting to the Biosphere’. AMBIO 40 (7): 719.

- Forstmann, Matthias, and Christina Sagioglou. 2017. ‘Lifetime Experience with (Classic) Psychedelics Predicts pro-Environmental Behavior through an Increase in Nature Relatedness’. Journal of Psychopharmacology 31 (8): 975–88.

- Foster, John Bellamy. 1999. ‘Marx’s Theory of Metabolic Rift: Classical Foundations for Environmental Sociology’. American Journal of Sociology 105 (2): 366–405.